Tom Entwistle gives his views on rent price inflation and the threat that rent controls bring to the rental market - for landlords and tenants.

For more than two decades now, private rents in the UK have largely tracked inflation. However, there’s been periods where rents have surged ahead. After the 2020 pandemic, we’ve seen sharp spikes in rent price inflation in the UK, driven by supply shortages and rising costs.

This leaves affordability for tenants stretched to the limit with many single renters and households struggling to find vacancies and pay rents, and many landlords exiting the private rented sector (PRS)for good.

Given the surge in rent price inflation, politicians — particularly in Scotland, but also in London, primarily driven by Mayor Kahn — are reviving the idea of rent controls.

The Housing (Scotland) Bill, now reaching its final stages in the Scottish Parliament, threatens to bring new powers to cap rent increases in designated areas, an idea that was implemented in the Irish Republic and partially in Scotland some years ago. The policy is politically popular, but all the evidence — from history and many international case studies — tells a very different story.

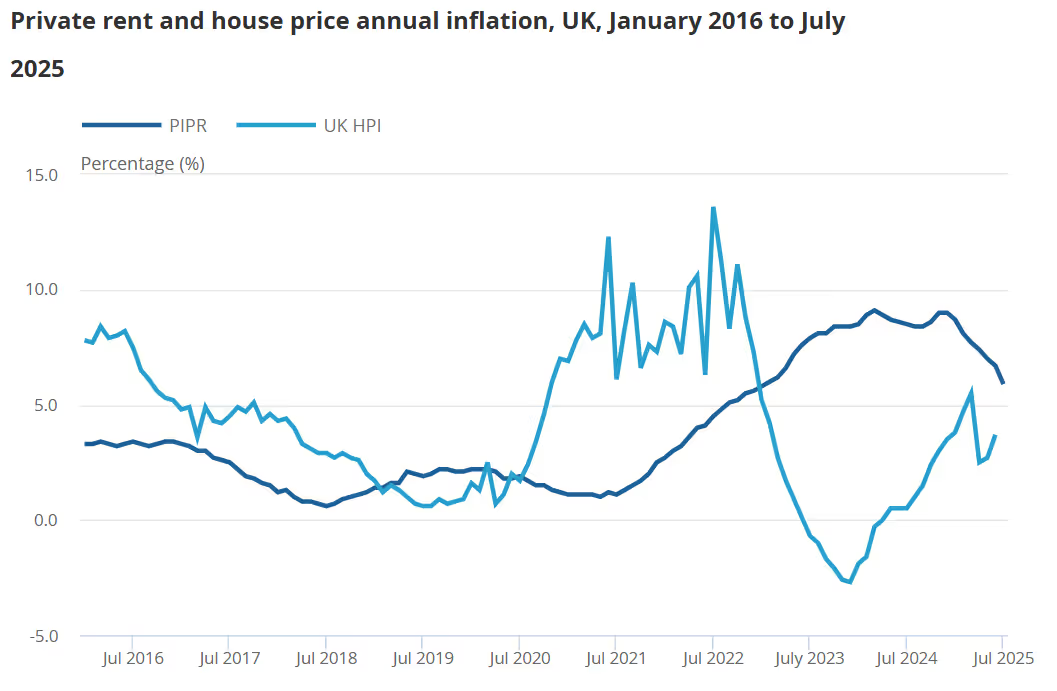

Look back 20 years and you’ll see a fairly even progress of CPI inflation and private rents. Rents rose cumulatively at around the same pace as general consumer prices for much of this period, that was until the mid-2010s. After 2015, and especially after 2020, rents began to accelerate sharply.

Between 2000 and 2025 CPI just about doubled (£100 worth of the CPI basket would cost £191.71 in August 2025) while average UK private rents rose by a similar amount, though with regional variations.

After the pandemic, rental inflation hit multi-decade highs, outpacing CPI and wage growth in many regions. London, Bristol, Manchester, and Edinburgh all recorded double-digit annual rent increases at times, making affordability challenging for many renters.

Rent as a share of income has risen steadily with the ONS and Resolution Foundation showing that median (middle earner) tenants now spend well over 30% of their income on rent in some major UK cities.

[Source: ONS - PIPR = price index of private rents, HPI = house price index]

The trend is clear: rents did not run away from inflation in the long run, but they have done so recently, as the supply of rental housing started to become constrained.

Demand for private renting has grown substantially in the UK over the past 25 years as the population increased substantially, but supply has been constrained and has failed to catch up. The result has been increased rent levels across the UK and particularly in our major cities, especially London. Following Covid and with life returning to these cities there’s been a dramatic recovery in tenant demand with rent levels surging sharply.

This situation has led to several city mayors and politicians calling for powers to allow them to freeze rents. It’s reigniting the longstanding debate about whether rent controls should be applied in England and Wales.

Whilst rent control may be a popular concept in the eyes of much of the general population, as well as those of many left-of-centre politicians, as a quick fix for a housing market in crisis. Thankfully more rational heads still prevail. It may be socially desirable to cap rents, but in reality, the costs have been shown again and again to outweigh the short-term benefits.

Ultimately regulations that impose rent control prove costly to administer and far from helping tenants in the private rented sector (PRS), they do more harm than good. Yes, there are some short-term hits that enable people on lower incomes to access affordable accommodation. They also prevent landlords exploiting their tenants and it reduces tenant turnover because they stay put when rents fall below market values: good for those tenants but bad for the rest, and the economy as a whole.

Now for the real negatives, and the unintended consequences of rent control. The main consequence is the long-term reduction in supply as landlords can no longer make a reasonable profit and simply leave the sector. Stagnant controlled rents coupled with price inflation and low profit margins mean landlords start to skimp on maintenance and repairs meaning properties fall into disrepair and further dilapidation of the national housing stock.

Control can also favour better off tenants with good steady jobs at the expense of lower income tenants and families, and experience shows that a significant “black” rental market always develops. Labour mobility is severely reduced, and inner-city housing is barred to new renters, which necessitates long commutes for productive workers.

So, the quick fix solution to a housing crisis has many unintended consequences and the side-effects of rent control are numerous and outweigh those initial benefits, which brings me to use the famous quotation, that old chestnut, by the social economist from Sweden: Assar Lindbeck, who stated "rent control appears to be the most efficient technique presently known to man to destroy a city—except for bombing".

His perspective highlights the real negative consequences of rent control, such as fostering discrimination, creating black markets, reducing the quantity and quality of housing stock, and inhibiting labour mobility as outlined above.

Other Swedish economists, a country that has long practiced rent control, including Gunnar Myrdal and Michael Svarer, have, in the light of experience, also expressed similar views on the detrimental impacts of rent control.

While rent control has popular support as a quick fix for ever rising rents, this does not go to the root of the problem. The real issue is the growing imbalance between the supply and demand for housing.

Unlike many other western nations, the UK’s population has been growing rapidly, mainly due to immigration, a situation that’s crying out for more rental accommodation. But contrary to all logic, government policy over recent years has largely discouraged further investment in the PRS by the small-scale landlord. Conversely, it has focussed on what is in comparison a miniscule sector of the PRS: the tax incentivised large corporate investors – the build-to-rent (BTR) sector.

Yes, the BTR sector will have an increasing part to play in rental housing in the UK in the future, but these developments tend to be at the premium end of the housing market, leaving the small-scale private buy-to-let landlords to service the bulk of the market - the middle and bottom end of this market.

Increasing supply does not have to mean building thousands of new estates covered with those shiny new red landscapes. Buy-to-let landlords, properly incentivised, will bring lots of older, and in some cases vacant, housing stock back into serviceable occupation. Unfortunately, successive governments haven’t seen it like that. They have positively penalised the BTL landlord with higher and higher taxes, high mortgage rates brought about by rampant inflation, and not to mention increasingly stringent and expensive regulations hitting the sector.

The appeal is obvious. Capping rent increases gives instant relief to existing tenants, particularly in high-demand urban centres. It’s an easy headline and it plays well with voters (and with the public at large) hit by rising living costs.

But the economics are equally clear. Controls are a very blunt instrument. They may bring short-term winners, but the longer-term consequences are consistently negative. They mean existing landlords exit the market; new investment is discouraged and consequently the supply of housing supply shrinks.

Of those landlords remaining, controlled rents reduce their funds for maintenance and refurbs, to the point where properties deteriorate. Tenants on low rents naturally stay put in the properties they’ve otherwise outgrown and ever fewer vacancies mean newcomers (students, young professionals, in-movers) are squeezed out.

This isn’t just theory. It’s a story that’s played out from Britain (the Rent Acts) to Berlin, from Stockholm to San Francisco.

Ireland provides us with a very recent live case study. In 2016, “Rent Pressure Zones” were introduced in areas of high demand in the Irish Republic, particularly in Dublin, limiting annual rent increases to a percentage above inflation.

At first, rents in controlled areas did stabilise relative to runaway growth elsewhere. But the unintended consequences of rent controls soon emerged. Supply dried up as landlords sold or switched to another business model, to short-term lets. Market distortions started to develop between controlled and uncontrolled areas and affordability worsened for new tenants, who often had to pay far higher market rents for scarce properties.

The Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) concluded that in Ireland, while RPZs gave temporary relief, they exacerbated supply shortages and affordability pressures in the medium term.

Scotland has already experimented with emergency rent caps during the pandemic, freezing rents temporarily but now the new Housing (Scotland) Bill could create permanent powers for rent controls in “designated areas.”

The details are still being debated, but the proposals include capping annual rent increases to CPI+1%. They may well be superficially quite reasonable, but long term they potentially undermine the rental market for landlords if inflation reverses and undershoots their cost base.

Industry groups in Scotland again warn of an investment exodus, with some of the major institutional investors and developers already saying they will steer clear of Scottish build-to-rent. Politically in Scotland however, the temptation to control rents seems irresistible, but for landlords, having a clear plan for the future, where rent flexibility may be gone, is impossible.

The short-term winners in this scenario will be sitting tenants in controlled rental housing, as ever the losers will be those new tenants seeking ever scarcer vacancies. In the long term virtually everyone loses. Landlords see squeezed returns, tenants face reduced choice, and quality suffers.

In reality, rent controls help the few today at the expense of the many tomorrow.

Reports spell out the negatives

Thankfully, the Welsh Government has recently rejected the calls for controls following the publication of its White Paper on Fair Rents & Adequate Housing, which outlines measures aimed at improving the supply and condition of private rented properties without the need for rent control.

Similarly, the English Government has rejected the calls following several reports including the House of Commons Library, Private rented housing: the rent control debate and an LSE report from 2018 by Christine Whitehead and Peter Williams, Assessing the evidence on Rent Control from an International Perspective

Increasing supply is the obvious answer. Create the right environment where private landlords can make good profits and thrive and supply will take care of itself. But for some unknown reason, buried deep in the UK psyche, encouraging and incentivising private landlords to invest and helping them thrive, goes against the grain.

Secondly, the Government expects the PRS to effectively become a provider of social housing on the cheap, through the housing benefits system. This is generally funded at a level that does not equate to a level that promotes a decent standard of housing. The Local Housing Allowance urgently needs to be uprated, and means-tested assistance applied.

Third in line is the taxation of small-scale landlords. This needs urgent reform to ease the burden, incentivise investment and stem the supply exodus. The Government is committed to increasing renters rights, some of which clash with those of the housing providers. Tip the scales too far in the wrong direction and yet again, private landlords will vote with their feet.

Inflation over the last 20 years shows that rents have broadly kept pace with prices. But when supply is restricted, rents inevitably surge, which has happened over the last few years, creating a rental housing crisis.

The cure is not rent caps; it’s creating the right environment where landlords can thrive, where they can invest and provide safe warm housing while making a reasonable return on their investments. Only the Government can create such a climate through sensible taxation and regulation policies. Creating a stable framework where landlords can plan and tenants can afford to live is the only answer to the housing crisis of 2025.

Rent control and landlord bashing are not the answer. They may sound good to the uninitiated, but their track record is clear: they reduce supply, they distort markets, and ultimately, they harm the very tenants they claim to be protecting.

[Main image credit: Markus Winkler]

Tags:

Comments